The Camera Sees…

Written by Chester Eagle

Designed by Vane Lindesay

Layout by Karen Wilson

Circa 4,780 words

Electronic publication by Trojan Press (2012)

The Camera Sees:

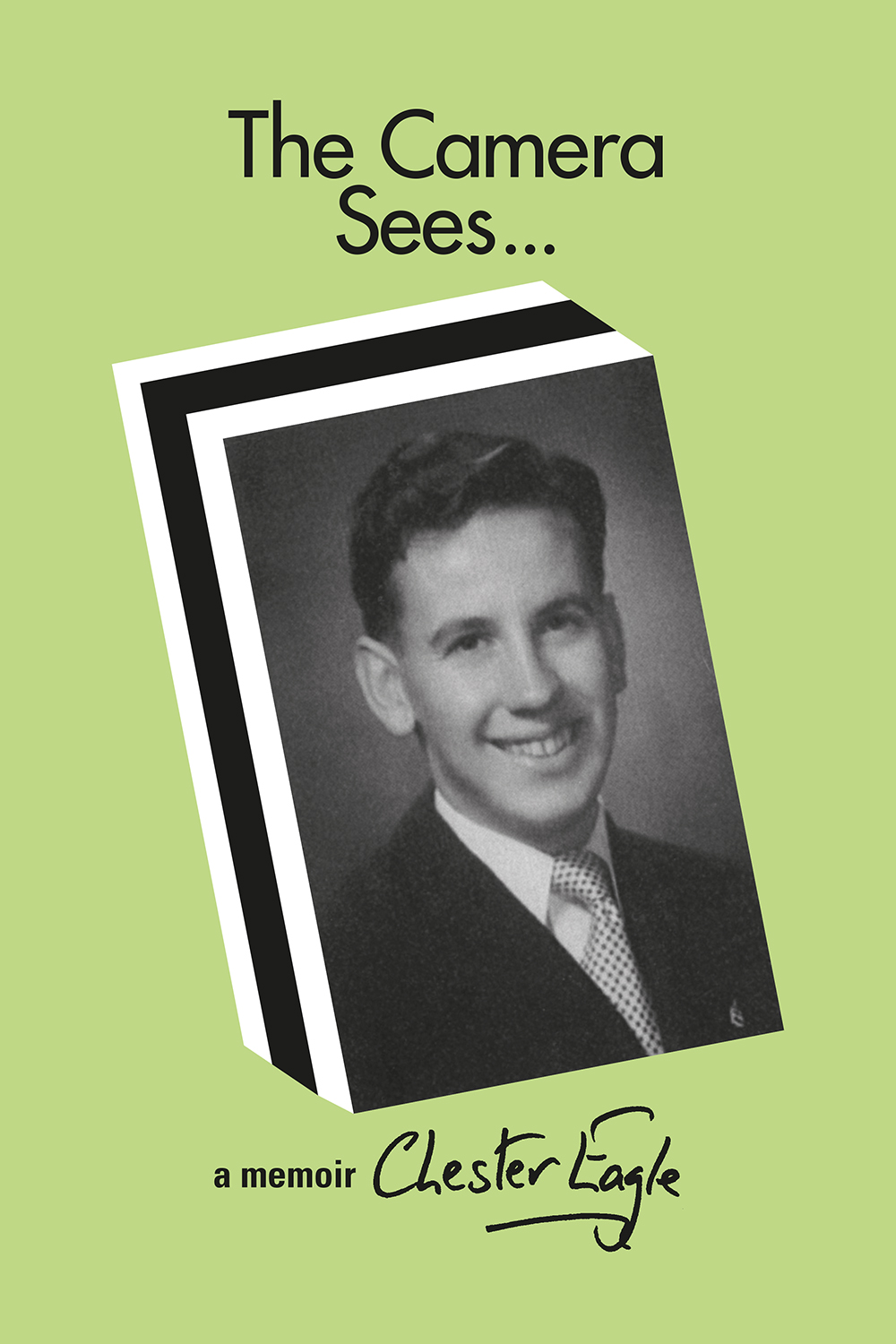

Ella Duncan, a sister of my mother, worked for some years in a fashionable Collins Street studio. She sat in reception, but also did retouching, and Mr Dickinson, her boss – always ‘Mister’ to me, because I was so much younger – had faith in her, as well he might, for she was extraordinarily capable. If I visited her East Melbourne apartment, I thought of her as mysteriously single, but at the studio she was the sort of person that successful businesses are built on. Single as she may have been, she thought of marriage, children, the family line, as central in life. When I left school and was about to start university, she arranged for me to have a portrait taken by Mr Dickinson, while a few years later she commissioned portraits of her two nieces by another sister, my Aunt Gladys. Della and Jill, my cousins, brought their graduation robes to the studio and their portraits were mounted, framed, and passed into the care of that branch of Ella’s family.

It is sixty years since my portrait was taken and I came across it the other day. I looked at the young man, with a head of glossy hair, and could hardly accept that he was me, and of course, he isn’t; he’s what I was a lifetime ago. Ever so many things that were going to happen to that young man hadn’t happened when he looked at the camera. Of the picture being taken I remember little beyond Mr Dickinson’s familiarity with his equipment. He told me where to look and he moved or altered the angle of his lights with an easy touch, and then he told me it was done. I had been represented for all time. There would be informal snaps to the end of my days, no doubt, but if anyone wanted to know what Chester looked like at the end of his schooling and the start of his university days, they could turn with confidence to the picture Mr Dickinson, with, perhaps, the aid of a little retouching by Ella, studying a negative carefully against the light, would produce.

I had been made permanent at the age of eighteen.

This, of course, is impossible. There are so many forces bottled up in eighteen-year-olds, waiting to be released, and events, relationships, achievements and mistakes, all queuing up to happen. Eighteen year olds have a world to deal with, or shape, avoid, or be hit by … as the case may be. And now, after this prelude, I suppose I must look at the portrait, and see what it says to me. The truth is, I’d rather leave it in the box where it’s usually kept, and pushed aside when I go looking for pictures of someone else. But it’s there, it’s the suavest, most professional picture of me ever taken, and it can’t be avoided. Ella wanted it done, so it could be given to her sister Alice, and mother needed it as evidence that her mothering, and therefore her life, had been successful. The picture was proof of something and I can’t avoid comparing the declaration, the intentions, embodied in the photo with the things that have happened in my life since that momentary click, and the affable wave of Mr Dickinson letting me know that I didn’t need to smile any longer.

I was free to leave behind the person that had been captured, and get on with whatever the future had in store.

Let’s begin. It’s not hard. The young man hadn’t married; indeed he was virgin. It wouldn’t be true to say that he didn’t understand women, because he knew very well where they belonged. In the world as he knew it, a simple rule obtained – men ran the world and women ran the home. A generation later, this came under attack from a new wave of feminists, but it was the way things had been done, everywhere around him, and he took it for granted. The picture shows him wearing a suit, and it was the last, and best, suit from his days at a famous boys’ school; more attention was given to boys’ schooling than to girls’, though there were a number of fine girls’ schools in his city, though how they differed from his own, he couldn’t have told you. Perhaps they didn’t differ at all? They certainly got results at exam time, and that meant something, but really, he didn’t know. He’d been to dances at these schools, and enjoyed them well enough: they linked in some way to the institution of marriage, and that was both universal and well-nigh rock solid. It was how everything worked. When you were young, it was your future. When you were old, it was your past. It was the full burden, to be accepted or veered around, by people – the sad ones, mostly – who hadn’t married. He didn’t know his future, this young man, but it surely had a marriage in it, and then he’d know.

Let’s look at him. He’s smiling, he’s confident. The world’s had nuclear weapons for a few years, but it hasn’t blown itself up. Communists and anti-communists are at each other’s throats, the world’s divided, but shops are still selling bread, people are still wearing badges relating to the things they believe in. Women – what was I telling you? – are dressing up for the spring races. There was a Melbourne Cup winner in the year the photo was taken, the year before, and the year after. The world might be groaning under its burden of self-destruction, but people were doing the usual silly things, and the wiser ones too. His mother had sent him away to school because education, she knew, was the key to the future and if he’d done well – his results would be out in a week or two, but he felt confident – then he’d move to university and, deus volens, he’d do well again. If you wanted to succeed, you picked your landmarks and steered by them.

His parents, he knew, had done well. They’d taken a struggling farm and made a success of it. They’d been able to pay for his education, though they’d wondered, at the outset, if they could manage. They had managed, they’d given him the best possible base, and he was ready to take the next step. Can we see this in his smile?

The next step. What we can see, if we study him, is the surety that if anyone looks carefully, and makes good judgements, then they will be all right. He’s certain, this young man, that pitfalls can be avoided, that disasters only befall those who aren’t looking, that the crashing and roaring of history’s storms don’t destroy everything, that Australia is a safe place. Order prevails down here because orderly people are in charge, or that’s how he sees it. It’s what he’s been told and his famous school has shown him how to make things work. So has his family. They know that you have to work hard, endlessly, but you don’t do silly things, you snatch opportunities when they come, you ignore the hopes that rise out of alcohol, you follow the rules, treat everyone decently, and wait!

Fortune, so elusive, is never too far away. It rains from time to time. The men of farming families, such as his, look at the sky to see if the clouds are hopeful, and occasionally they are. When they’re not, they go back to work as if things may change before their debts are piled too high. Patience is the virtue everyone says it is. Most if not all the vices are destructive so virtue is the better bet, boring as that may be. The long run is the only race to be in. Dreamers have foolish hopes of racehorses making them rich, or lottery tickets solving their problems, but life’s a long haul and only those who never give up can expect to die happy. Steadiness and purpose are the things that bring you through.

Can you see these thoughts in the young man’s mind? Perhaps not, but you may be sure they’re there. It’s not so much that he thinks these things as that he’s absorbed them. They are part of him though he only partially knows.

He hasn’t been tested yet, though he’s sat, and passed, any number of exams. Exams, tests, don’t only search you out, they teach you as well. They tell you what the world wants to know about you, and if you’re smart you use one exam to make you more ready for the next. The world’s not shy about telling you what it wants. It wants you to take one of the paths that lead to success, and it’s good at disguising these paths, so that you wonder if you’ve chosen well, and then, when you’re on the verge of giving up, it gives you your reward. It’s what happened to his parents, when their farm started to make money. This came about because the price of wool went up, and that was because America was fighting a war in a cold country and wanted to keep its soldiers warm; Australia’s wool was in demand, the farmers who grew it found cheques in the mail and its small farmers as well as its station-owners were a class with money. This young boy in our photo could tell you that a year earlier he’d had to fill in a form which included the question ‘Father’s occupation?’ and he’d written, ‘Grazier’. Not farmer, no: social distinctions were part of the awareness of his famous school and he didn’t mind conforming. It was a way of staying with the pack and he wasn’t about throwing away advantage. ‘Grazier’. It kept him with the boys who came from bigger properties; distinctions were made in the mind and if you didn’t let them in, you kept them out.

That was what smart people did, though you knew that gaps could open up between people’s ideas of themselves and their surrounding realities: you had to be careful that this didn’t happen to you. Vigilance! You had to be watchful, and this young man, under the observation of Mr Dickinson’s camera, knows what’s being done to him. In being recorded he’s being made part of his generation, and this means being known, identified … allocated a place, really, and places, like marriage, are for life, don’t forget. The game is more than a game, it’s a roulette which is not only Russian, but universal, it’s played in Australia as it is everywhere else, he’s in it, and he didn’t even hear a click when Mr Dickinson pressed his button, if that’s what he did. The picture was taken and there he is.

What does the camera see? It’s a good question. The camera sees, but it doesn’t know. It records, showing what it can, but the rest is still to be told.

Let’s look again. His tie is white, contrasting with his blue suit, but does it? It’s white with royal blue squares, and royal blue is the colour of School House, where he lived as a boarder. White is, after all, the opposite of black, or navy blue, the colour of his suit. He’s announced his freedom by moving to the opposite of what he’s been wearing the last six years; what sort of declaration is that? Years later, at a writers’ festival, he runs into a fellow Old Boy who’s now a writer, and they tell each other that they can’t wear colours, they never wear colours, some vestige of the uniform is in their clothing still.

At the time the photo is taken, he’s proud to be part of the tradition. It would be fresh in the mind of this young man that when he went back to his home in New South Wales, having left school at last, he took with him an Old Melburnians tie, and wore it, walking along the driveway of their home, and he wore it, one evening, as the family sat down to dinner. His parents made no comment because they weren’t sure where the conversation would go if they raised the matter. He only does this once, but it’s a sign that tradition has claimed him, at least for the time being. When, and where, will it let him go?

The school he’s attended loves success. Failure or disgrace quickly reveal that its attentions are not charitable. Let the school down and you’ll be offloaded quickly. There will only be a splash as they toss you over the side! Your job is to bring credit to those who attach credit to you and it’s a system that works when everyone pulls in the same direction. Old Boys need to keep an eye on those who are leaders, or in some other way focal. It’s simple enough and it means you always go for advantage. Mr Dickinson has a photo in the foyer, a couple of paces from where Ella Duncan sits, of Robert Gordon Menzies, Prime Minister of Australia; it was taken in the same studio as our young man: the two of them would have sat in the very same chair. There’s no caption under the PM, nothing beyond the evidence of his patronage. Mr Dickinson needs to make no bigger claim than the picture of a superbly self-confident man, and it’s in the studio, not – for this would be vulgar – in the street below. You need to come in to know that you are in.

What does the camera know? It sees, but can’t foretell. If you question it, there’s no reply. It’s waiting for those internal forces to come into play with the world about them. This young man expects to marry, but doesn’t know who it will be. Years later, his wife says to him, unhappily one night, ‘I’ve met my match’, and this divides him, because he’s made from his mother’s as much as from his father’s likeness, and if his wife says this then he’s out of balance with himself: his mother might have made the same complaint. He’s proud, as he sits for the photo, and in the decades that follow, of the men of his family, but then, every family is made from an importation, if that’s the word, of women – wives, mothers – who marry into the family, take it over and change it. It’s an illusion that the family line is passed down by the males. Families are recreated in every generation by the understandings, the feelings and experiences, of the women who marry in, and in doing so, change the thing entirely. Women then, often enough, appoint themselves as the guardians of the family story, they write its histories and they tell its tales. Outsiders?

In – ?

He hasn’t come to realise this yet, the youngster in our photo. He’s the product of a system that concentrates on the perfecting, or at least the considerable improvement, of the male. He honestly and firmly believes that women must adapt to suit their men. It’s the men’s job to be as good as possible, as worthy, let us say. Women, knowing this, know they must be clever, adaptable, ready to give ground on anything, so long as they keep their long-term purposes clear. This is how things are done. The women of his own family are genial, for the most part, enjoying such prosperity as may come their way, managing their menfolk; it’s what they’ve been trained to do.

But what about passion? The men and the women of his family would say that passion needs to be kept under control. A little of it goes a very long way. It’s a path to foolishness, and that’s an enemy of survival. Passion swirls like a sandstorm, obscuring everything. Passion makes people unreasonable; they don’t know when they’re making mistakes. They lose sight of everything but the object of their passion, and nobody can last for long like that. Passions upset the world, they don’t help it to work as it should. Wise people keep passion under control. Love should never get out of hand, though it should be used to develop the coherence of families, because it’s families that prosper, that last, rather than individuals. Properties must be developed, certainly, but then they must be handed on, and it’s this need for continuity that matters. Families depend on it, and this means they must know who they are. Hence the importance of the women’s role as keeper, narrator, of family lore. He doesn’t know much about this, the young man in the photo, though he’s the product of it. He’s very happy, as a child, when his father’s family are around him; somehow he trusts them more than his mother’s family, though they too are interested in him and want him to find success. Perhaps it’s because he’s male that he’s happier with his father’s people, because boys outnumber girls in his father’s generation, and the opposite’s the case on his mother’s side. Perhaps: who can say?

Not the camera; the camera doesn’t know. It records what it sees, but it doesn’t interpret. Even Mr Dickinson can only do a little of that, by choosing poses and putting his lights where he does. He’s a genial man and wants his subjects to look their best, so he doesn’t enquire into their troubles. The studio produces positives rather than negatives, if we may put it that way. People come to Mr Dickinson to have him get the best he can from what they offer, and he’s good at this. There are pictures all over his walls, look at them. There’s the PM, and a few other figures of repute. Reputation’s important, it’s the way we’re reported, and that’s the way society sees us, because it mostly repeats what it’s been told. So the photos are messages fed into society’s stream, telling the world what we are, inviting them to have a look.

There are photos in the reception area of Mr Dickinson’s studio, and my aunt is, in a sense, their keeper. If you ask her who this person is, or that, she will tell you, always respectfully. She may have worked on the photo, if it needed retouching, and she will have encountered the subject when he or she came in. She will know who they are and will seat them, even making tea, if they have to wait, or she will pass them straight to Mr Dickinson if the studio’s free. There’s a social ease, an accomplishment, in the art of reception, and Aunt Ella has it, certainly. It’s one of the reasons why I like to go there, if I’m in the city on a Saturday morning. I often visit the city, but Ella belongs, and it’s her function that makes her part of the place. Melbourne’s small enough, and class-divided enough, for it to matter who you are. Having your photo taken is a way of conferring identity on yourself, and it matters, it really does. Look about you, look at the people on the walls!

Do we know them? No, we only know how they present themselves. If there’s any scandal about them, that’ll be reported in a paper called The Truth: such a name, such a reputation! Having your photograph taken is part of the virtue industry; for vice, which also pays, you must go elsewhere. Truth is a euphemism for scandal, so it’s looked down on, but the photos taken by Mr Dickinson veer in the opposite direction, showing his subjects in the best possible light, or rather, light and shade. He uses those lights with skill, and chooses his angles to show us in the most pleasing way!

The camera sees, but doesn’t know the future, so what does it hold? This young man who hasn’t worked yet, apart from helping his father on the farm, doesn’t know that when he finishes his career as a teacher he will have to look after his parents in their old age, ever conscious that those who nurtured him when young now need nurturing themselves. He will do it willingly enough, and yet reluctantly, because it isn’t easy to accept that life itself is a burden: who thinks that when they are on the verge of what they hope will be marvellous, and fulfilling? His future is out of sight, so he doesn’t know who he will marry, or the trials and tests of his personality that marriage will bring. He approaches it as his father did, but times have changed, and the male authority of his father’s period has long since disappeared, and he has to suffer from the shortcomings of his all-male schooling. How easy, how simple and clear-cut everything looked to his school. Men behaved in manly ways, and women in their more elusive, emotional, sympathetic way, and thus the two lived happily! He has friends, his friends have mothers, he knows how women live in the circles in which he moves. He rather envies women because they can use parts of their personality that males keep under lock and key. Women are, in a way, to be envied, but men have a duty to keep the world rolling properly, and this means sacrifices: not for nothing is it the duty of men to fight when their country calls. His school sits beside the Shrine of Remembrance, he hears the bugles every Anzac Day, he knows what they mean, and hopes they’ll never call for him …

But they might!

So he’s afraid of the warlike nations that hurl themselves into conflict as if the desires that bring lives to a brief and sudden end can’t be controlled, when he thinks they can. He’s aware, this young man, that restraint must endlessly be exercised, or how will all the finer achievements of civilisation be carried on, even developed, as he hopes to do in whatever career may come his way? There’s a future in front of him, and he has to take charge of it, yet, although he doesn’t know it, this is one of the hardest things that anyone can attempt to do. When he and the wife he marries have eventually separated, and he realises that most of the causes of the failure can be sheeted home to him, he determines that one of these days he will try again, and this time he’ll succeed in offering perfect love. His opportunity comes, he finds himself in love again, and this time he’s old enough, and knowledgeable enough, to shed perfection like a light in every corner of the new relationship. The love he shares with his new lover is perfect, but then it appears that perfection can’t sustain itself for very long if it clashes – as it does in her – with other needs: in this case, for a younger woman to turn herself into the sort of mother her own mother has been. He – the young man in the photo, now turning fifty – works on the perfecting of the relationship, while she, still struggling to know what her path will be, weeps at the sickening knowledge that she’s already committed herself, through her children, to being a mother, and the essence of this function is self-sacrifice. In ignoring the promptings of her heart she is making herself able to be what she senses she is destined to be.

So they will part, this couple we are talking about, the second, the female, of whom is not yet born when Mr Dickinson’s photo is taken in his studio, with his bulky old camera using glass plates, the camera that recorded Bob Menzies, you remember, so his picture could be hung, an advertisement really, on the studio wall, inside reception, where Ella Duncan soothes anxious customers and clients, and organises everything so that Mr Dickinson’s job is easy. The young man, our young man, with his royal blue and white tie matching the blue suit of his school, will have to cope with the loss of the love of his life, and, strangely, in a truly mysterious way, he does. The love, intensely-focussed, that has blazed in his life for three years, moderates, changes, and turns itself into a compassionate, tender affection for the whole of mankind. Loving everybody instead of somebody, he finds peace. He is able, now, his life adjusted, to go on. He stops thinking of throwing his life away. He has a son and daughter to care for, he has books to write, he has the whole of humanity to bring into consideration. That part of his life which he thought would go on forever will not; he must be ready for whatever comes at him, to him, next.

He is, he does. His photo, if we had one taken at this stage, would show a different man, watchful, considerate, tactful, all the things he wasn’t when he was young. Mr Dickinson likes people to put on their best possible face for his camera, but this implies a choice, that’s to say, they can decide what to show the cleverly-managed lens, but the truth is that most of us can’t. Things happen to us, we cause things to happen to us, acting with a minimum of self-knowledge most of the time, and then we cope with what follows. This is usually a process of catching up with what we hadn’t foreseen; pursuing pleasure, obeying pride, we bring on ourselves things we weren’t expecting, and they give us shocks. Our lives aren’t what we expected. This is when we react to the confidence in our children’s voices with words of caution or restraint, the children react in the ways of young people and we know that contrary to the expectations we had of endless movement in the direction of something progressive, chasing and reaching eventual success, we have found ourselves as bound as all the generations before us to the lottery that hands us the fate we have to accept.

The young man in Mr Dickinson’s photo doesn’t know what’s in store. How could he? Mr Dickinson doesn’t know; it’s not his job. Aunt Ella has asked him to do a portrait of her nephew, at a reduced price no doubt, for she is valuable to him and he most certainly knows that making her happy is good policy. The young man doesn’t know, the camera doesn’t know, for all it can do is record, and it certainly can’t predict. The winds that blow in rumour and expectation know more than the lens at the front of the bulky wooden box, with its shutters, bellows and the rest of it. The camera focuses on whoever’s sitting in the chair, and each of them, one after the other, brings their own fate and fortune with them, attached, but in some mysterious way not available to their consciousness. Why can’t we dodge our futures? Why can’t we control? Answer – most of us try, but we’re dealing with the unknown, all the more difficult to manage because forces as yet undiscovered are in play. We won’t know how to deal with them, we may not know that they are there, until they reveal themselves …

… and then the picture we have of ourselves will change. We’ll look at the photo taken decades before and deny that it’s ourselves as we know ourselves to be, today. I am not that man, that woman, we will say, putting it aside in favour of something a little more up to date. That will leave us open to the unsettling awareness that there is a connection between our present selves and the person in the photo, but what that connection is, and how it affects the person we are today, we cannot know. We don’t know who and what we are, although it’s gratifying when our friends say things about us that we recognise, or like … We don’t know who we are, and we’re grateful to a camera that tells us, so long as it shows us nicely, because we’re mysteries to ourselves. No wonder we hold people like Mr Dickinson in awe, or scorn those artists whose portraits of people we admire we happen not to like; our faces are only masks hiding the unknowable, and the camera appears to take away the guesswork and give us something we can believe …

… even when we know it isn’t so.

The writing of this book:

Another pair, something I seem to like doing these days. The relationship this time is more discursive than with Chartres and The Plains, but both Four Last Songs and The Camera Sees … range across a life’s span. The life in question, which happens to be mine, is considered, first, from a musical vantage point, then reconsidered from the point of what, and how much, can be revealed by a camera portrait. Not so very much really, in the case of the camera. I think what’s common to the two memoirs is their concern with how little we understand when we are young. The camera looking at the young Chester may show him better than he knows himself – this is an open question, I suppose – but it cannot know, any better than he does, what’s to happen to him, and as for the previous memoir, the young man who listened to the German composer’s late songs simply had no idea that they would become as a permanent point of reference in his viewing of the world.

How could he know anything like that?

Another thing I need to say is that I am growing old and can no longer produce such complex works as my novel Wainwrights’ Mountain. I can’t see such things ever coming again. I’m too worn out to produce anything so big, but then again, I don’t need to. I wrote that book when I needed to unify my vision of the world, and that’s been done. Now I can enjoy the liberty of producing fragments, confident that they fit together in some way, and offering them to readers to examine and see what they can find.