A Certain Class Of Men

A Certain Class Of Men:

At the end of every afternoon Father milks our cow. I like to watch this in a disinterested sort of way. One afternoon, however, he gets the milking started, then turns to me. ‘I’ve got something I need to do at the haystack, Ches,’ he says. ‘See how you go at finishing the job.’ He gets up and I sit on the stool. Father walks away and I try to continue the milking. I’m not very good at it, and then a thought comes into my mind. If I do this, I realise, the job of milking will be my job, daily, forever. No! I sit for a minute and then I go to the haystack and tell Father the only lie I can remember telling him. ‘I’m no good at it,’ I say. ‘I can’t get any milk.’ Father tells me not to worry, he’ll finish the job in a minute, and he does. Do I watch him the following day, and the day after? I can’t remember, but I do remember – I can’t forget – that I changed the direction of my life that day.

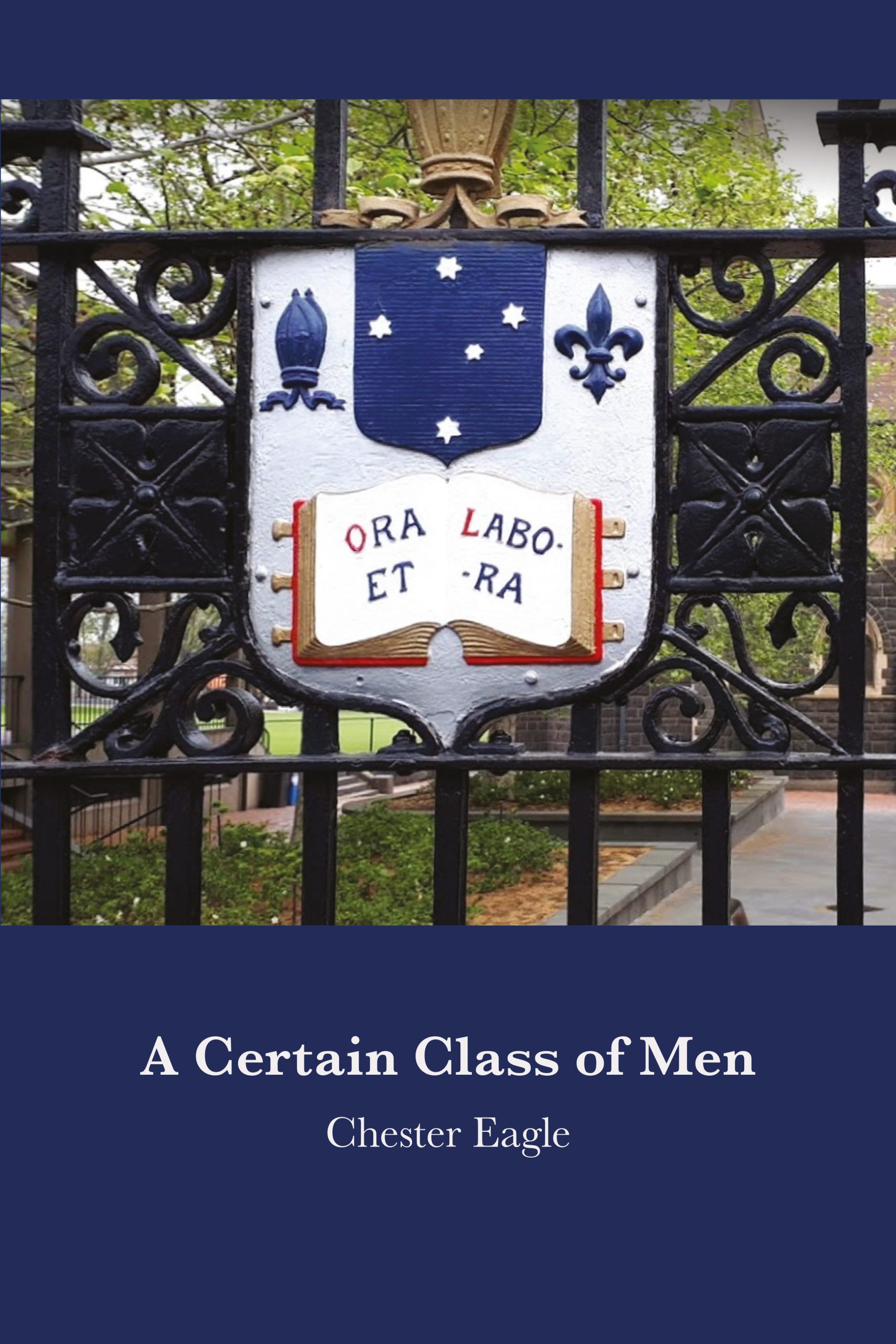

Lying in bed one night I overhear my parents talking. Mother wants to send me to school in Melbourne. Father says this will be costly. ‘Norman,’ Mother says, ‘I will pawn my wedding ring!’ Father refrains from saying that this, though a spectacular sacrifice, won’t cover a term’s fees. I am deeply moved. It’s my future they’re discussing. Melbourne Grammar. Mother doesn’t want me to be a farmer. Finley school is limited; I’m to go away for a real education. A letter is sent, an application form comes back. My headmaster writes a reference which I read without recognising the boy he describes. I’m accepted. There’s a list of clothes that a boarder will have to bring. Mother writes to Myers and a parcel comes back. So much navy blue. I tell Father that I prefer the red (cardinal) of Scotch College. He chuckles. ‘You’ll have to wear whatever the other boys are wearing.’ I accept this without having any idea of how much more I will need to do by way of fitting in. The famous school has handled would-be individualists before ever I came along.

In August 1945 I’m listening to the news on ABC radio. The announcer tells the world that a new bomb has destroyed the city of Hiroshima. Hardly a building has been left standing. I stare at the trees at the beginning of our avenue. The Japs will surely surrender? But this is not what I’m thinking. In fact I’m not so much thinking as feeling enveloped in gloom. The world has changed in some way that neither I nor anybody else can understand, or predict. The world is different now, and the change is enormous.

As the days pass I recover my spirits. I walk in the paddocks as often as I can. There is a feeling of security in their spaces, and Mother and Father are central to them. Father is responsible for everything to do with farming, and Mother with the house. It’s a simple division of the man/woman partnership and it works. I, however, will be going away. Father comes to my room one night as I’m lying in bed, and he tells me the time when he’ll wake me in the morning to drive us to Melbourne so I can start my new school. ‘It’s going to cost us a lot, Ches,’ he says, ‘maybe more than we can afford. We’ll see how we go for a year, but after that, if we can’t afford it, you’ll have to come back to the farm.’ I tell Father that I understand this. I will accept whatever happens. I’ve never been away so I’m not afraid of coming back.

The move, when it comes, doesn’t displace our farm and surrounding country as my base. It’s there and can’t be dislodged. It underlies my Melbourne schooling and later travels to Europe, America and China. I look at the world with the land as my starting point. The plains between Deniliquin and Barham, where Father’s family live, are flat, with distant horizons, mirages of floating water, and the wonkiest, wobbliest-looking telegraph poles crossing the limitless space. Flatness is somehow fundamental in the making of my mind. I see the world as normal when it’s flat, to which we could add dry, largely without humans, populated by saltbush and sheep, with any housing which it may possess pushed to the horizon. Anything else is a change, a visitation, another thing altogether.

My parents drive me to my new school. Mr Down, the principal, greets them, then indicates that I should follow Miss Niblet (pronounced nib-lay) to the clothes room so she can show me where the contents of my case will be stored. This means pushing through a pair of elaborate doors that separate the principal from everyone else. I hesitate, I tremble. On the far side of the doors I will be separated from my parents, my life in New South Wales and will be … where? I push the door and go through.

Blair Culross, from Moulamein, New South Wales, has the bed next to mine. Matron shows us how to make our beds with hospital corners, and we’re told to strip the bed every second day and turn the mattress upside down. This, though we don’t realise it at the time, is a measure to allow the mattresses of bed-wetting boys, if there are any, to dry. One of the boys notices that there’s a strange building not far from our school. We get used to passing it when we go to Alma Road for a milkshake, or sweets, on Sunday excursions. The street’s named after the mansion, which has a row of elaborate, and I think concrete, storks ornamenting the balustrades. Labassa! Years later I encounter it in Kenneth Slessor’s Five Bells, and later again I go through the house, admiringly, when the National Trust opens it to the public. At this early stage, however, all it does is signal that Grimwade boarders are surrounded by things unknown in the places they’ve come from.

Grimwade is the development of a mansion and grounds given to the school by the family of that name. Surrounding streets – Alma, Inkerman, Balaclava, Sebastopol – have names known throughout Britain’s empire from battles of the 1850s Crimean war. Mother spends my entire first term with her sister Gladys, in an apartment close to the school. Boarders are not allowed out for the first month, but after that settling period she takes me out each Saturday. On the first of these occasions I ask her to take me to the Albert Ground, in Saint Kilda Road, because I want to watch the district cricket final: some of Father’s passion has entered me. We catch a tram, we watch Essendon playing Melbourne, and the Australian test bowler Fleetwood-Smith is last man in for the latter. He swipes wildly at one ball and scores a boundary. He tries again, and is out! I’m amused, I’ve enjoyed the play and the manner of his dismissal makes the day. We go back to the school. Harold Stanley, a stout little man in charge of boarders, greets Mother most amiably. Have we had a good day? She says we have, says goodbye, and leaves. Stan then turns on me. Was I not aware that the senior school’s third eleven was playing Wesley at Grimwade that same afternoon? I was not. Well, I should have been. My first and only loyalty is to the school of which I am now a part! I think this is silly but I have learned by then to say ‘Yes sir.’

We have an hour’s study after dinner. It’s called prep, and is supervised by one of our day masters. On the evening I have in mind, the master on duty is Taffy Evans, a small man with enormous enthusiasm for teaching French. He delights in the language, explaining the forms of verbs and comparing them to the related activities of English verbs. This I find interesting. On the evening in question, however, I’m reading about the solar system, something equally absorbing. Taffy, I notice, has left the room but this is of no consequence. We’re all busy, and quiet. He reappears. He accuses a boy sitting near the door of talking. What if he was? Taffy disappears for a moment and comes back with a cane. He orders the talking boy outside, bends him over and whacks him twice very hard. The boy sits down, not quite in tears, and Taffy prowls the aisles, looking over our shoulders to see what the rest of us are doing. There’s a smell on his breath. He’s been having a few sherries with Stan. We’re sullen, scared, and seething. This isn’t fair. The school expects a lot of us but if we have to obey the rules, masters must do the same. It might be a hard bargain but it’s the one we’ve signed on to and Taffy’s broken the rules, not of kindness, or compassion – we can’t expect them all the time – but he hasn’t been fair. Fair! Fair, you hear us, Taffy? Fair!

At the end of my first year, Mother comes down to stay with her sister Gladys. I’m there one morning, reading the paper, when she asks, ‘How did you get on in your exams?’ The school had placed me, because I’d not previously studied Latin or French, in class 5B, an undistinguished group of scholars, with Harold Stanley as our form master. A double dose of Stan. ‘I came equal first,’ I said. Mother was delighted. ‘Who were you equal with?’ The boy’s name was John Sykes. He was quiet, I hardly knew him; I would have described him as being ‘all right’. No further could I have gone, but Mother was curious. ‘Tell me about him.’ I couldn’t. Mother, nevertheless, remembered his name. For years afterward, till I was in my forties, she would ask for news of John Sykes. I had an idea he’d studied medicine at Melbourne University when I was doing arts, but I couldn’t have told you if that was so or not. For the next twenty five years, however, I was coupled, in Mother’s mind, with John Sykes, who was promoted with me to 6A, then the senior school, and then … who knows? Not me. But John was my alter ego in Mother’s mind, my ghost, for years to come.

In my second Grimwade year my dormitory is a former army shed set in the mansion’s grounds. There are twelve of us and we sometimes talk after lights out. One night somebody raises the question of whether or not the universe is infinite. This sets us thinking, but we simply cannot imagine anything without a final boundary of some sort. But, as one of our number points out, it’s just as hard, just as impossible, to imagine a finite universe because, this boy says – his name’s Mickey Knight – if you get to the barrier, the wall, the signpost that says you’re at the end, you have to face the question of what’s on the other side. None of us can see an answer to this. We don’t realise it but we’ve pressed against one of the limitations of the human mind.

Father visits twice in my Grimwade years, once on the day of the house sports. He stands on the edge of the oval with, of all people, Stan beside him, talking. What on earth can they find to talk about? On the other occasion, he takes me to watch a wool auction in a steeply raked auditorium, the auctioneer facing a scattering of buyers. They, like us, have been to the warehouse and inspected the wool, thousands of bales, all marked with the growers’ names, stretching away in lines. They bid, some noisily, some with signs. We wait until our wool (NPE Nairana) is sold, then leave. Father’s happy because we get a good price. He’s reminding me, I think, of how the family can afford to keep me where I am.

We shower before we go to bed. There’s an endless supply of hot water, and we scamper about, having lots to say. Nakedness is natural. Stan, fully dressed of course, supervises. He urges us to wash thoroughly but not to stay too long because it’s almost bed time. This is fair enough for the boarding-house master, but from time to time he announces that if we think he’s watching us too closely it’s for our own good because if anything’s not right in our development it’s his business to have something done about it. Eh? Then comes the Friday night when one of our number in the army shed is away for the weekend and Stan arrives a little before lights out in his dressing gown and pyjamas. He’s going to sleep in the vacant bed. Eh? He does so, and the night is uneventful, but … eh? Many years later an Old Melburnian of my vintage tells me that Stan, facing certain charges, has chosen to hang himself.

During a holiday soon after I reach the senior school Father takes me to see Doctor Middleton, a Deniliquin doctor who practises one day a fortnight in Finley. ‘Just a check-up,’ Father says, ‘to see that all’s well with his development.’ Doctor Middleton has two sons at school with me, both excellent swimmers. He takes my temperature, puts his stethoscope here and there, examines my tongue and prods my body in various places, then he starts to talk with Father. He has recently bought a farm near Deniliquin and plainly knows little about farming. He has many questions for Father, who tells him what he should and shouldn’t do. This takes perhaps half an hour, though the waiting room is full. Eventually we leave, and Father pays the receptionist half a guinea – ten shillings and sixpence. This seems unjust to me. Doctor Middleton got much more from Father than he gave. I say nothing; Father seems content with the visit.

In my first year at Grammar I meet the Macfarlan boys, Hamish and Andrew. They’re from Sydney but their father and uncles are Old Melburnians and they’re sent to the school as boarders. We do lots of things together and their mother, Joan Macfarlan, invites me to stay with them in the new year. This will involve travelling, at the age of thirteen, to Narrandera on our local diesel and then catching an overnight train to the capital, which will be new to me. Father books me in a sleeping carriage, and I share a four-bed compartment with three men far older than I am. One of them takes an interest in me and makes sure I know what to do. Father has already given me a few shillings in silver because, he says, the steward for the sleeping car will be standing at the door when you get to Central Station and you must hand him a tip. I do this as to the manner born. The Macfarlans are waiting with their new Jaguar and drive me to Point Piper which I, in my ignorance, take to be any old part of Sydney. (It’s years before I understand that I have been welcomed by privilege and wealth.) I love Sydney because the Macfarlans are gracious hosts and want to show me everything. We go to the Gap, to lunch in a city restaurant, Kings Cross, over the Bridge, and so on. Years later, when I go to Paris, I have to see the Eiffel Tower. I’m that sort of traveller, or I was. Sydney enchants me. Cities need to be different and the alleged rivalry of Sydney and Melbourne has no place in my mind. Besides, I am a New South Welsh boy and that’s something that’s lasted to this day. The Macfarlans’ apartment building has a lift and a pool, and standing on the jetty which is one side of the pool I see a shark in the harbour waters. It’s a far cry from Finley! Yet when Hamish and Andy, on a later holiday, visit our farm, they’re as enchanted by country life as I was by their city. This has been a wonderful basis for a life.

Back home on the farm I unpack a present I was given in Sydney. Hamish and Andy had been given roller skates for Xmas and by the time I arrived, they were fast and skilful skaters. Joan Macfarlan, knowing that I was coming, had bought a third pair of skates, and I had managed to move about with my friends, though without their speed and mastery. We explored long stretches of Point Piper on these speedy devices, and I was looking forward to rolling about the farm. I strapped on my skates and headed for the avenue between our pepper trees. The wheels were reluctant to turn, even on the fairly hard surface of our avenue. Bitumen was needed underfoot, or concrete. I looked about. There were a few yards of concrete between our house and the outside toilet and laundry, and there was nowhere else, on the whole of our farm, where I could roll! My disappointment was huge. I yearned for the city by the harbour with ships entering and leaving. Things happened in the city, and Sydney had been mine for a fortnight, beaming and glowing beyond the balcony where I and my friends had slept, and now I was back in our insignificant little town, one of the tiniest parts of the aggregation called New South Wales. It was humbling. The place I came from had no significance, even though our wheat fields prospered and the sheep grew wool which was shorn at McGill’s shed … No, I couldn’t make Finley seem important after my introduction to life overlooking the harbour. Father had told me about the horseman from the New Guard who cut the Harbour Bridge ribbon with a sword before premier Jack Lang could do it with official scissors, and again I wondered why the dramas that made life exciting all happened somewhere else.

Two apparently unimportant seeds are planted on that first trip to Sydney. The Macfarlans have a tiny gramophone and they play a record of the Blue Danube waltz, with an orchestra conducted by Arturo Toscanini. I’ve heard the Blue Danube in all sorts of versions, but this is something else. I know Toscanini only by reputation, but, ignorant as I am, I can see that he is a musician of another sort. The name sticks in my mind and when I hear announcers say his name, I listen. The other concerns Winston Churchill, hero of World War 2. Hamish and I hear a recording, or possibly a broadcast, of famous wartime speeches, and we’re amused by the intensity of the man. We imitate him as a private joke between us. If we see a plane in the sky, one of us will say, ‘Never in the whole history of human conflict have so many owed so much to so few.’ We imitate the prime minister’s pauses, emphases, and intensity. We think we’re funny. But years later I acquire a disc of his speeches and am amazed to find how well I remember them. Unforgettable! ‘We will fight them on the beaches … We will never surrender.’ The one that hits home hardest is ‘If Britain and her empire should last for a thousand years, men will still say … this … was their finest hour.’ The passion and conviction are extraordinary. As I write, people are trying to pull down or deface statues of the man. He was no doubt as fallible as any of us – the Gallipoli landing was one of his bright ideas – but unlike most human beings he had a time of greatness, inspiring his people. ‘We will never surrender …’

Father comes to Melbourne for some reason, and stays at the Victoria Coffee Palace. I meet him there and we’re picked up by his friend Ray Hutchinson, by now a wealthy man. He takes us for a drive through leafy streets and fine homes on spacious grounds, then, before we go elsewhere, we return to the Victoria because Father needs something. He leaves Hutch, as he calls his friend, and I, and goes inside. I’m in the back seat of Hutch’s costly modern car when he half-turns, and says over his shoulder, ‘Your father’s going to make a success of that farm.’ I’m amazed. I take our farm and our fortunes, whatever they may be, for granted, but Ray Hutchinson thinks differently. Money has to be made, either by being smart, by hard work, or both, and he’s thinking about his friend, and has decided for some reason to share his thoughts with me. I suppose I’ve been thinking that Father’s already a success, but Hutch thinks differently, and when money is the topic, Hutch, I know, knows.

Our masters all have nicknames. Lofty Franklin teaches maths, Greasy (who isn’t) Gardiner physics, Charles Howlett (French) is known as Chazzer. Geoff Fell is Lippy, Spike Jones gets his name from a band leader of the time. John Hunt, our flamboyantly dressed teacher of literature, is known as The Enthusiast (because he is). The Perry housemaster is Mouse McKean. Referring to these people by their nicknames is a sign to each other that we’re insiders. We know who’s who, giving deference where required. It’s not cheeky, it’s a way of expressing our acceptance of who and what they are. Old Boys ask us how Tickle’s getting on and we know that they know how we feel about this master; it’s a way of telling us that we’re replacements for them, sitting in the same seats, doing the exercises they did: it’s an important part of the tradition we belong to, and that’s perhaps the school’s greatest strength.

I come home from Melbourne one term holiday and Mother gives me a list of things to get at Sammons Edwards store. ‘And while you’re there, Chez,’ she says, and I know something more important, more Mother, is about to show itself, ‘Go into the Ladies department and say hello to Lola Gatley. She’s engaged to … I don’t think they’ve set a date for the wedding yet, but it can’t be far off. Before Christmas I’m sure.’ I say I will. I get the supplies Mother’s asked for, then I carry my basket, bag, or whatever it is, into the Ladies section, and there is Lola. Her father is our butcher, I’ve been in his shop often enough, now his daughter’s getting married. I am, perhaps, seventeen; Lola’s the same age as me. She was with me in classes at Finley State and then Finley Rural School. There is something lovely, because ever so trusting, about her. Her face is round, with a dainty chin, and her hair is fine and blond. It’s tied with a small and simple ribbon. ‘Hello Chester,’ she says, ‘how are you getting on at school?’ I tell her all is well, though that’s not entirely true, then I ask about her coming marriage, and I wish her well. If there is a conversation in my life that I would like to have had recorded and played back to me now, as I write, it is this one. It only lasts a couple of minutes, and I’m sure it’s trite and obvious, but it is a parting. Though Mother has sent me away to Melbourne, I remember the people I was at school with in Finley, and I still feel part of them. Lola’s about to be transformed by accepting the life of a rural woman, partner to a man, and I’m headed somewhere else. The boys at Melbourne Grammar are far more ambitious than Finley people, and the weddings I see coming out of Saint Peter’s chapel have a glamour and an air of social triumph not to be seen in Finley. Yet Lola is curious, and truly wants to know what I’ve been doing, where I’m going, and what it’s been like for me. I’m humbled, I’m admiring, and I feel that what she’s doing is a triumph too, or at least an assertion, perhaps the only one she will ever make, perhaps the first of many if her man’s not strong, or successful … Life’s a gamble, and she’s about to make her play; has, perhaps, made it already by committing herself, by saying yes. I leave the shop with my confidence untouched, but feeling also a sense of loss, and I never see Lola again.

Senior school boarders are enslaved by rituals. They have us in their grip night and day. There are so many roll calls that we hardly notice them. We’re not allowed out of bed before 7.30 and there’s a roll call at 7.55, followed by breakfast. We have to read the notice boards several times a day because we’ll be punished if we don’t obey an instruction pinned to the relevant board. Punishment may mean a Saturday morning detention (two hours) or it may mean a caning, most likely delivered in the boarders’ shower room, a resonant place where the sound of a belting carries out to the quadrangle which is the heart of the school. Boarders play quad cricket there, using a tennis ball, with an ancient lamp post as the wicket. Custom rules. When there’s a wedding at the chapel, and that’s often enough, boarders love to glimpse the glamour, with its hints of sexuality, of the bride, groom and party. We stare, but from no closer than that lamp post which is our wicket. If the tennis ball hits the post, you’re bowled. If you’re caught on the first bounce, you’re out. You don’t have to be a good cricketer to enjoy the game. Big hits bounce off the quad walls and bounce again on the corrugated iron lower down. Mobs of boys try to anticipate where the bouncing ball will land, and luck may favour the small and skill-less as often as the skilled. It’s odd that this most central game, played in the heart of our prison, gives us our most exuberant feelings of freedom.

Yet the monastic life has benefits. We are so close to each other – too close – that we get to know each other better than day boys do. We can see our masters’ qualities and weaknesses. We are cruel in things we say. Nicknames are savagely used. The slightest deviation from standard behaviour is drawn attention to. For all this, we have to accommodate each other, and we do. When we see each other away from school, we’re generous, gracious even. Our habits of study are good because we’re supervised at prep. We don’t waste time. We learn proportion, and how to dismiss trivia. We’re reasonably forgiving and our understandings, so brutally applied as boys, will benefit us as men. We’re very proud and know how to avoid shame by succeeding in one way or another. What are known today as problems of adolescence hardly exist because the process we’re in is one of taking us as individuals and turning us into a certain class of men. In that sense our heightened awareness of each other is a support, a benefit making the path a little easier. Our complexities are subsumed into the process of which we’re a part. There is always a correct or at least a normal thing to do. This means that we can’t fail to understand or at least have sympathy for the rebels whenever they appear, as appear they must because our regime is strict. Confident that we are born to rule, we can’t avoid a few thoughts about what it’s like to be ruled. Why not? Because we are being ruled all the time. It’s a very thorough-going system that we’re in.

Bully Taylor, coach of the first XVIII, has connections at the Melbourne club, and Grammar’s home games are sometimes played at the MCG. A group of us are walking home after one of these games, and we’re dawdling because we’re in the Botanical Gardens, Melbourne’s heart, when we hear a bell ringing. We know what this means. The gates are being locked and anybody still inside should get themselves out! But Grammar’s won the footy, we’re in a good mood, and we can’t be bothered hurrying. We stroll to a gate and yes, it’s locked. Not to worry! We move along the boundary fence and find a suitable spot, get ourselves up and over, and jump to the grass below. Five minutes later we’re in the quad, in plenty of time for dinner. Yet there was a moment, I recall, when we thought we were locked in, and the gardens seemed, not exactly hostile, but mysterious, containing, perhaps, some numinous force which might surprise us. This didn’t last but it was strong while it had us in its grip.

In my final year I get the job of timekeeper for the first XVIII. How this came about I can’t remember, but I recall sitting with my fellow timekeeper from another school beside the great bell that began and ended quarters at the MCG. The place is quiet enough with only a few hundred boys in the huge stands, but I ring the bell for half time with enormous vigour, and Babylon, Brian Hone, our new headmaster, is most amused. He’s sitting one or two seats from we timekeepers and he thinks my bell-ringing is funny. He has a jovial, rumbling laugh, and I, in all my seriousness, am not sure what I’ve done that’s amusing him.

We read Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan. I’m impressed, and even more by the GBS style of preface writing, In later years, when I’ve begun to see myself as a writer, I have to throw off his influence on my prose, but I haven’t reached that stage yet. Mal Vercoe, our year 11 English teacher, finds himself one morning with a few minutes before the end of the period, so he tells us to write ‘Something. Anything you like.’ I write a few lines about Norman Taylor, who has the farm next to ours. Norman has been a champion footballer, Finley’s best, and sought after by seven of the twelve league clubs at that time. His brother was a fine player, and they played together in the ruck. In my piece about Norman I compare him to Jack Dyer, Richmond’s famous hard man. I‘ve seen a photo of Jack and think the two resemble each other. Mal gives us five minutes then asks ‘Who wants to read?’ I put up my hand. Nobody else does, so I get to have my say. ‘What do you think of that?’ Mal asks, and a boy says something critical. ‘I thought it was rather good,’ Mal says, the bell rings, and that’s the end of that. The school’s very proud of itself. Photos of victorious teams adorn the walls of the dining room. Our history’s everywhere. This sits awkwardly with many pre-modern features of the school. One telephone serves the senior boarding house, and it’s near the Headmaster’s study and Council Room where hang portraits of the school’s headmasters. A boarder’s placed in the Council Room every night to answer incoming calls. If it’s a parent ringing a boarder, the duty boy will go to room 17, where prep is done, to get the person required. If it’s someone – a man, and a vulgar-sounding one at that – wanting to speak to a maid, the duty-boy simply calls down the passage to the maids’ quarters. There’s no going there! The maids, and even more the men who ask them out for an hour or two, represent unmodified sex, and this has no official place in our lives.

It’s a church school, so sex is officially placed within marriage; this is more implied than said. There is of course an underground view. Bully Taylor, coach of the First XVIII, runs a boarding-house in South Yarra. It’s a haven for young old boys and, if the stories we hear are true, young women who are willing to put marriage aside for the excitement of a bed. One of my fellow boarders likes to talk about a successful naval (navel) encounter without loss of seamen (semen). We laugh at this. We know full well we’re being controlled. Funnily enough, we put this sort of talk aside when we go to dances at girls’ schools, as we do, even boarders, who’re called on to act as blind dates. It’s good being with girls. We talk freely. We listen to what they say because it’s different from our talk: more inward, more personal. Our rather frightening headmaster (The Boss, Joe Sutcliffe) tells us that it’s more appropriate to invite girls from one of our ‘sister schools’ to our school dance rather than girls from elsewhere. With women as with everything there’s an inner circle as well as an outer. Old Boys train for their football and perhaps athletics on our grassy oval; there’s a feeling that if you’re an Old Melburnian you don’t have to grow up except in ways that will be demanded of you in the senior positions you can expect to reach. That’s when a good wife will be important. We should therefore marry well but on the way to that desirable – and necessary – situation almost anything’s allowed. So long as it’s kept quiet! So women – and our lot attend those girls’ schools – are desirable, necessary, must be respected, et cetera, but there’s no interaction between their world and the inner bastions of our bluestone pile. They do the adapting, we push straight ahead. Or this is how it seems to me, many years later. I wonder what you think?

The East dormitory oversee the boarding house as once, we are told, the North dormitory stood over the school. This small group of boys watch us for any sign of weakness in our desire for our school teams’ success. Grammar (navy blue) must win, School house (royal blue) must win. We must yell, clap and barrack as loudly as we can. We must know the scores, who’s in the teams, who’s captain, vice-captain and third man. These positions, apparently, transform those who hold them. When Grammar (or School house) is playing football, we pack behind the goals, cheering every score. When the quarter ends, we get ourselves to the other end as quickly as possible, ready when play resumes. Boys in the East are our enforcers. They’ve got their eyes on us, appraising our loyalty, and ready to call us slackers. We fear being called to the East because we know what will happen. We’ll be shouted at and every aspect of our loyalty, our knowledge of who’s important will be examined. Boarding house masters must know what’s going on because when the East is in full cry their yelling can be heard throughout the school. It’s deafening. It’s approved of in some way, something to do with the English tradition of using boys’ brutality to maintain an order above which the teachers can perform their function. When a boy joins the East, he’s watched as he moves his things. He may take his clothing with him but he’s leaving much of his humanity behind. Then a strange thing happens. Without any prior warning or consultation, I’m promoted to the rank of probationer. Fred Jarrett, my housemaster, has been told to do this by Babylon, Brian Hone, the school’s new, and eventually greatest, headmaster. As I walk into the darkened quadrangle after this announcement, a young boy from the junior boarding house puts his arms around me. I’m touched by this and remember the moment still, after all these years.

Many things are done by rote. Jack Brooksbank, himself an Old Melburnian, takes us for Divinity. He walks in, textbook in hand, sits, and announces the page. ‘Who wants to read?’ Someone volunteers. The reader reads until either Jack or a boy raises a question. It’s simple, boring and without a hint of difficulty. Nothing gets talked about unless someone wants to talk. But one morning something in the reading calls up a question in Jack’s mind. He tells us that he was on a plane flying through the New Guinea mountains with some Japanese prisoners on board. The pilot gets worried because the plane’s losing altitude. ‘What would you have done in our position?’ Jack asks. Most of us are silent, thinking about this, but one boy says, ‘Chuck’em out!’ Jack nods. ‘That’s what we did,’ he says, and the lesson goes on as before. Lesson? We’ve certainly learned a thing or two, that morning.

My promotion means I change my place in the dining room. I move from further down the table to sit beside Simon Close, the prefect who heads the table. He’s a fine sportsman and clever in his studies, one of those who fit the school’s values perfectly. He tells me, when I meet him years later, that he loved his school years. Plenty didn’t. I think of a boy called Fascoe Fleay, son of a well-known naturalist, one of those who never fitted in. Walking the bush with his father, examining birds, animals and flowers, he may have been at home, but among the harshly judgemental boarders, he was nothing, nobody, a fool, an outcast. He was not alone. To survive in our school you needed to be clever in class, a fine sportsman, or preferably both. Simon was both, and I envied him his ease, his comfort. Now I was sitting beside him.

There’s an unexpected side to my promotion. I decide to read the Bible from first page to last. We are a church school, so as a boarder I attend chapel four times a week. Over the years I’ve listened to many passages of the Bible read in services and I decide to take an extended look for myself. It takes weeks, but when it’s done I take a list of questions to the chaplain, the Reverend J.C.W. Brown, a man of unquestionable sincerity. He sees it as his duty to give the best answers he can to the things I ask. I go away full of respect for him, but my belief in Christianity is much reduced. The superstructure which the church has built seems not to match the foundations of Christ’s teachings. Under the influence of Bernard Shaw, Shakespeare and just about everything I’ve read, I find myself moving away from what I hear in chapel and divinity classes, and looking for something more secular to give me answers I can live by. In later years I find this in a variety of places, most notably The Mass of Life by Frederick Delius and the Inextinguishable Symphony of Carl Nielsen. More of music later. Another change that comes over me in the last weeks of my school days is an acceptance of what the school has done for me. Much of what it stands for I reject, but everything it does is done well. There’s an authority, a dignity, in the way it operates, a level not apparent in the government school system that I can see. Much of this, I decide in later years, comes from the voice, the use of the English language in the King James Bible and the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. I hear passion, eloquence and some undefinable verity of consideration in those sources. The men who wrote them meant what they said in a way that the modern world can’t reproduce. Everyday speech and writing seem shallow beside these utterances from centuries before. Can people today believe what these things say? Every Wednesday night the master on duty, Geoff Fell, sends us off to supper with a brief recital of words that have never left my mind: ‘Almighty God, forasmuch as without Thee we are unable to please Thee, mercifully grant that Thy holy spirit may in all things direct and rule our hearts.’ We say amen and go for supper. We leave the school and, in my case at least, the words ring down the years. English is a noble language, for all its cobbled-together-ness. It has a tradition that the school has managed to embody in a way that is, it seems to me, superior to anything offered by anyone else. My search for meaning has made me come to terms with the school. I disbelieve in much of what it believes but I have absorbed the quality of its belief. There’s no room for mistakes, wastefulness or oversights in the way it does its business.

In some way which only becomes apparent to me in later life, Mother’s choice of school was appropriate. Mother believed in refinement and was never at home with anything coarse. She believed, and perhaps this means she hoped, that Melbourne Grammar School, with its reputation for being the top of the tree, would ensure that I became the sort of person who would rise in whatever profession I undertook; Mother hoped that would be teaching and was pleased when I took up that work. Father, on the other hand, came from a family which, without any pretensions to social class, was proud of itself because it never did anything in any way but what they thought was best. The Eagles had pioneering attitudes; that’s to say, they didn’t expect to live in circumstances of wealth or completeness, because life, to them, was a work in progress, and you were always close to the roughest and coarsest of those around you … but you stuck to your standards and didn’t let yourself down. A great deal of this had come down to me. I was rising to Mother’s ambitions, but I was maintaining the Eagle family stance of hauteur without height. So in the end it was Father’s outlook, the Eagle family outlook, which caused me to fit in at the famous school more than Mother’s Duncan ways. It may seem strange to bring in these observations at this point in my recall of six years at MGS, but I need to explain to myself the combination of sadness and pride I felt in the last weeks of my schooling, and the weeks that followed, when I’d left.

The school year is over but the dining room is still open because it takes a day or so for the boarders to disperse via the trains, planes or buses that will take us to our scattered homes. I’m standing in the quadrangle when Simon Close, shuffling his feet and looking tired, comes through the passage beside the dining room stairs. ‘Where have you been?’ I say cheerfully. He tells me! With his school days behind him, he’s asked Phyllis, who’s waited on our table, out for dinner, and after that they’ve spent the night at a hotel. I keep my amazement to myself, and chat with him as he goes to his study. I tell him I’ll be catching a train to New South Wales in the morning, but will be back in Melbourne to enrol at university, and I’ve heard there’s going to be a performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni. I’ve never seen an opera and I’d like to give it a try. Simon says, ‘When you know when it’s on, tell me, will you. I’ll come with you.’

We take balcony seats in the Princess Theatre, a quaint old gem of a building. Simon is attentive, and I am entranced. Madamina, il catalogo e questo. Finch’an del vino. La ci darem la mano. The statue warns Giovanni, then claims his soul. A trapdoor opens beneath the Don’s feet, and he falls into hell. The other characters line up to say what they’ll do now his threat has been removed. Donna Anna tells the man who loves her that he must wait until she’s recovered from what they’ve been through. This will take at least a year. Don Ottavio, who gave us Il mio tesoro an hour earlier, accepts because he must. Is this silly? Things are different in the world of opera? Yes and no! Simon and I emerge into Spring Street, opposite state parliament. Such things couldn’t happen here! Yet I feel that the opera has been true in some way I haven’t had to deal with before, have hardly even known about.

A Second Don

The overture tells you some of what’s going to be enacted, and the first scene, ever so brief, plunges you into the story. Mozart was a great dramatist. More than that, he has music to aid in what he’s doing. He thinks in music, which means he transports us to a dimension quite different from the worlds of law, morality, or even common sense. The characters express themselves supremely well, they’re free in their imaginations, and hence in ours, to live in the only way they can. The opera’s sub-titled Il Dissoluto Punito, so that’s simple enough: the villain will get what he deserves. But that’s not how the audience sees, feels, experiences it. Donna Anna’s father interrupts The Don, swords are drawn and in a moment the old man’s dead. A few quiet notes as the scene dies away tell us how seriously we’re to watch what follows: judgement’s premature till we’ve experienced what’s yet to be shown.

Experienced is the word. The composer (and librettist Lorenzo da Ponte) don’t let us decide quickly. Their technique? It’s as old as time: it’s the power of story. Story’s not the same as rhetoric, though it may employ it from time to time. Indeed, what’s an aria if it’s not a supreme example of (musical) rhetoric? I said Mozart was a great dramatist; he’s also a trickster. Notice that the Commendatore is hardly dead before the Don’s servant, Leporello, is giving the nearly-ravished Donna Anna a list of his master’s conquests. Notice also that word; conquests. It’s not the same as rapes! His aria’s funny. It’s told with relish. The old man might be dead, but, sad as that might be, he’ll be no more than a line in Giovanni’s catalogue unless something happens. This is the power of story. What will happen, and what will be the connections with what’s already happened?

We may make up our minds at the end of a story, but not before. Judgement has to be suspended; that’s the trick of a good story and this is as good as they come. What will happen next? Don Ottavio will assure Donna Anna that his love is steadfast. Nothing has changed his love for her, and his wish to marry. The audience can’t help wondering if Donna Anna may not have sent some signal, perhaps unintentionally, of desire for the Don. Why else was he breaking into her room at night? Without any encouragement at all? The audience is uncertain; this is the power of story, letting us be sure of some things, not of others. The question’s important, and Ottavio’s lovely arias – whoever heard anything more beautiful than Il mio tesoro? – don’t give us any answer. The Don must be gotten rid of. The threat has to be removed. The threat, you notice; any of us might be tempted, if the Don set out to charm us.

Enter Zerlina and Masetto. Enter the Don again, interrupting a wedding, something he could only get away with because of his noble status. In no time at all, an advantage of a speedy story, Masettto’s brushed off and the Don’s singing a duet with Zerlina. It’s worth pointing out that he’s not only wooing Zerlina, he’s seducing the audience as well. Rapist? Ravager? Not if you listen to this ill-assorted couple. Who wouldn’t succumb to the charm of Mozart’s music? Is it unfair of me to say this? No. One of the reasons the story’s so well told, and the opera’s so great, is that all sides get a chance to have their say. It’s notable that although we see the Don in action, he never bothers – as Mozart/da Ponte present him – to justify himself. If he did that he’d be accepting the right of others to judge him and, if they so decide, to punish. Donna Elvira has her say, as do Donna Anna and the loyal but timid Ottavio. Leporello knows the Don’s heartless, but he sticks by him, admiring the bravura of the man, just as the audience does. A mob of men go looking for him, and what does he do? He tricks them into thinking he’s Leporello, then divides them: let half of you go this way, and half of you go that. Even the statue of the dead Commendatore, warning him in the graveyard, is no more than a curiosity to this courageous, perhaps invincible man. It takes a supernatural power, a power from beyond the grave, to bring him down. He’s enjoying his supper, you remember, puts aside a warning from Elvira, who surely loves him still, and faces the statue on pretty close to equal terms. Repent? Be buggered. Repent? No, never. To hell he goes and the dissolute is punished at last, but it took more than earthly law or power to do it. There’s a mighty challenge in the presentation. Heaven, or something representing its power, is needed to bring him down.

Justice? Yes, what we call justice has been done, but maybe justice is no more than what’s needed to level, or equalise, what nature has made unlevel and unequal. The fact is we’ve watched the Don in action and he’s won us over. Stories are powerful. Well told, they force us to face the truth of our reactions. Dramatists do this all the time but when it’s done through the music of one of Europe’s greatest geniuses, it’s hard to avoid being convinced.

The writing of this book:

I moved out of my home of fifty-two years and into a small room on the eighth floor of a new building housing the elderly and the infirm. My good friend Brad Webb soon had my computer set up. I felt a wish to deal with my life’s experience, even though most of the major events had already found their way, in some form or other, into books or mini-mags already published. A new way had to be found. I decided to start with my earliest memories and then see what surfaced next. Things popped up from many points in my life. I was surprised by what did and didn’t push itself forward. My teaching career stayed in the background for the most part. Many good friends kept themselves away from observation, while what seemed to be somewhere between minor and trivial came well to the fore. I accepted this, while I also felt an occasional need to emphasize some area of my life that seemed under-represented.

I also felt a need, once in a while, to write an essay of sorts about some feature of my life that I felt needed emphasis. Hence the essays, if that’s what they are, dealing with Don Bradman and Don Giovanni: a contrast I find amusing. Something else that I find satisfying when I turn the pages of this work is the fairly objective tone of voice employed, right from the start, in dealing with things which are in many cases extremely personal. I’m not sure what the reader will think, but I feel that the writer allows quite a number of his defects to show.

In doing so, of course, I can’t help but show the personalities and possible shortcomings – as they were to me, at least – of those with whom I had close contact, and I felt uncomfortable about doing this, since they didn’t get any right of reply! I decided, therefore, to publish, initially at least, only a couple of sections of the book which I felt would cause no adversarial reaction: hence the mini-mags The Don and A Certain Class of Men.