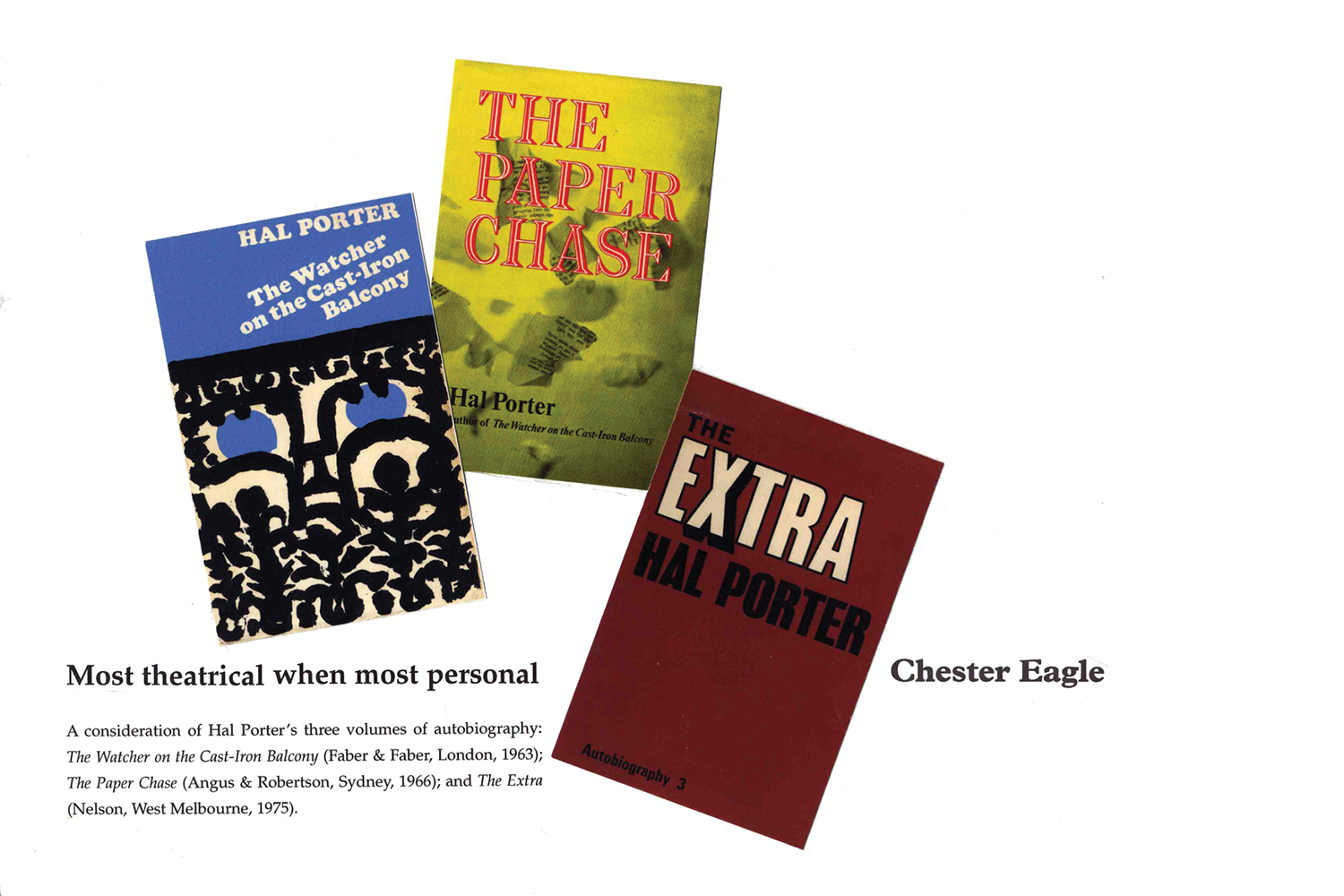

5. Most theatrical when most personal

5. Most theatrical when most personal

A consideration of Hal Porter’s three volumes of autobiography: The Watcher on the Cast-Iron Balcony (Faber & Faber, London, 1963); The Paper Chase (Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1966); and The Extra (Nelson, West Melbourne, 1975).

Most theatrical when most personal:

In his third volume of autobiography Hal Porter says this:

T. S. Eliot says a writer’s progress is an ever-increasing ‘extinction of personality’. You take it he means that, as a writer ages, he’s progressively less curious about himself, more and more interested in clues to other natures: their possessions, fads, frenzies, accents.

A little later, he adds:

Let this be made clear: the main reason for writing outright autobiography wasn’t exhibitionism. An account of anyone’s life to the age of eighteen is hardly attractive or thought-provoking. The young are like uncooked scones, unset jellies. I wrote autobiographically because it seemed the most convenient way to record ‘my generation’. In this I’m no Robinson Crusoe …

He goes on to list a dozen Australians who wrote autobiographies within a decade of his first attempt on the genre, but reveals more a couple of pages further on, when he says:

It’s the Past, distilled, bottled (literature doesn’t exist without artifice), which is eau de vie, the cognac of existence. [read more]

Introduction:

In 1981 Patrick White published an autobiographical book called Flaws in the Glass; the Melbourne Age commissioned two reviews, one of them from Hal Porter, who said, among many things unflattering to ‘Mr White’:

Writers of my sort can be said not so much to read as to examine another writer’s work rather as one car freak examines the vehicle and driving of another car freak. One says, “Splendid vehicle! Superb driving!” Or, “Nice vehicle! Ghastly driving!” Or, “Can’t stand that kind of cumbersomely pretentious vehicle! And what bewildering and erratic driving!”

Hal confesses that the third attitude is his to the novels and plays of ‘Mr White’. I will say no more at this point about Mr White or Mr Porter, but I quote this comparison of writer and car freak because in the essays that follow I am the freak who comments on others of his kind. I know I can’t see my essays as others will see them but I imagine some readers accusing me of many things, and others, well trained, perhaps, in one or another school of literary or social criticism, who will think my observations no more than shallow or ignorant. To such people I can only say that these essays offer whatever it is that a fellow-writer can offer, and don’t pretend to offer anything else.