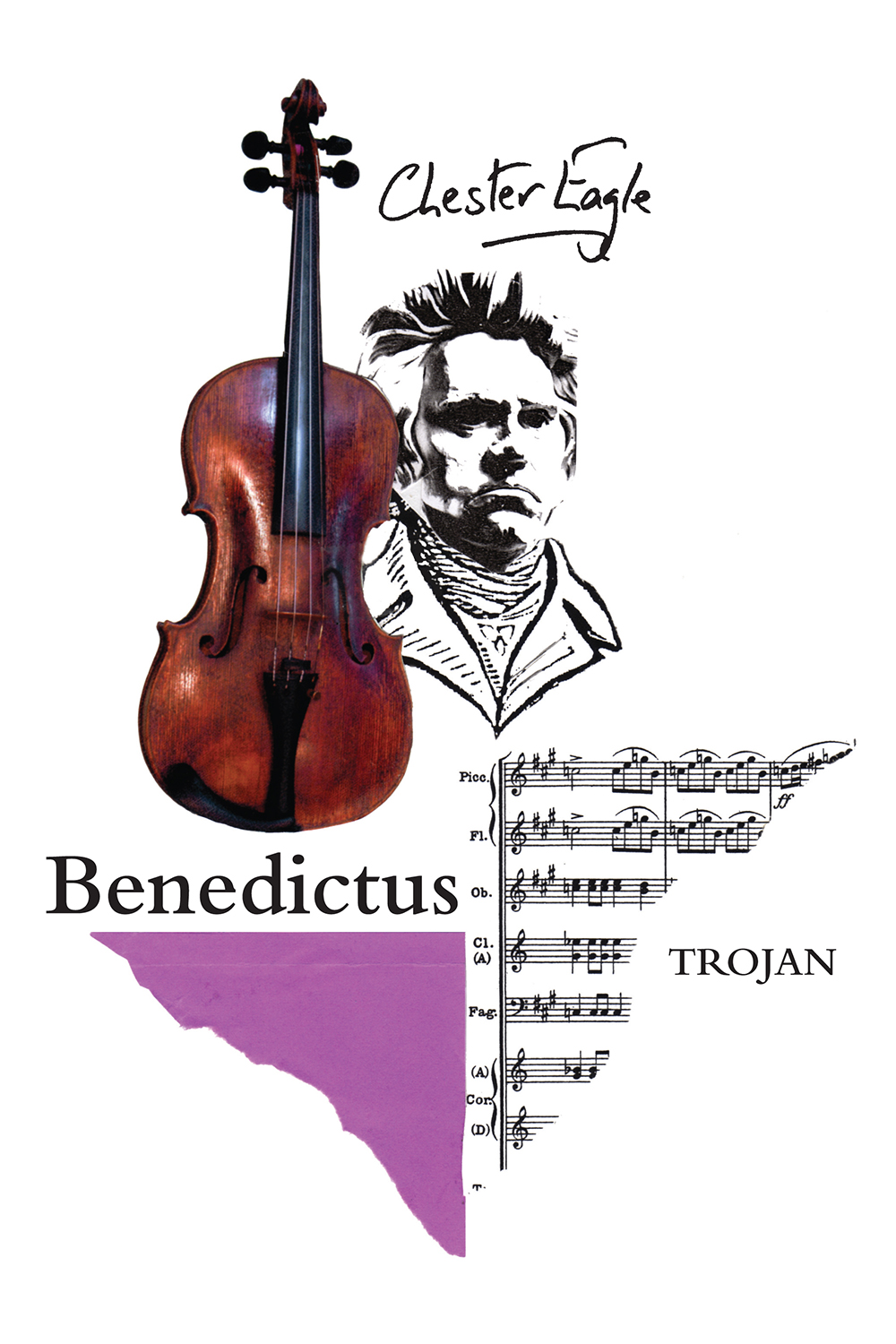

Benedictus

Written by Chester Eagle

Designed by Vane Lindesay

Layout by Karen Wilson

Circa 29,500 words

Electronic publication by Trojan Press (2006)

The writing of this book:

This book was written quickly. My earliest notes were written on 8/10/2005, the first essay on 22/10/2005, and the last essay was finished on 7/1/2006. Three months from go to whoa! The reader will notice that lengthy passages are brought in from earlier books, so there is a sense in which I was summarising rather than writing. Nonetheless, the usual formative period was quite intense; it took ten days to grope my way through from a ragbag of ideas to the sequence of the final work, and even then my writing was dogged by a feeling that I ought to have been writing something else. What right did I have to discourse on mysticism? I’d been attracted to it as a young man, I’d never taken this aspiration very far at all, so what I was offering was no more, I felt, than a heap of substitutes: the experiences you have when you don’t have a mystical experience. This disowning of what I was doing was genuine, keenly felt, and accurate, I think. Nonetheless, I could not stop my underlying suspicion of, or aversion to, mysticism coming through the pieces I was putting down. They are what I truly feel, and I think that one of the things a writer has always to do is to put down things s/he feels to see how others react. We are rarely the first or only people to feel in a certain way, and it is only by the expression of ideas which may make their owners uncomfortable that useful discussions can begin.

Writers need nerves, and sometimes stomachs, of steel!

I also found, when I had finished, that I was very pleased that I had moved the subject matter of this book from the themes and approaches of almost everything I’d written before: I say this even though the essays are full of quotes from things I’d written earlier. By putting these scattered thoughts together I was making a new agenda for myself and any readers who’ve bothered to stay with my writing thus far. I was pleased to have broken out of a clichéd form of myself.

A word about method. In the first essay, about a boy cycling home into an approaching storm, I refrained from trying to make a statement on behalf of the cloud above the child, tried, too, not to give the child any awarenesses beyond his actual experience at the time. It seemed to me that it was enough to look up, again and again, to reflect from here and there, because in that way a little more of what was hovering in the sky might be understood by the reader who wasn’t there to see it and the old man who, as a child, was. I thought this was the best way to keep the writing clear, and pure: Orwell’s pane of glass it isn’t, but I hope I’ve learned a little from that master of clarity in prose.

Lastly, a word about music. Few people can write about music, yet it seems easy to me. My advice? Never try until the music is as familiar as the furniture of your rooms – because it is the furniture of your mind – and then, when writing, never try. No controlling! Sit there, ten fingers extended above your keyboard, and see what comes out. Mozart and Beethoven weren’t afraid to improvise, jazz musicians do it all the time, and so should you. Go for it, friends! Even if you make a mess, it won’t do you any harm! And I suppose I have to admit that music seems better adapted to the expressions of sensations that are so inward, or so unusual, that we call them mystical. Most writers, I suspect, envy the fluidity, the infinite changeability of music, bound, certainly, by the instruments’ capacities and their players’ techniques, but we writers who use language are bound by our materials, our medium, and the words and grammatical structures we use are developments, at best, of the words and sentences used by everyone who uses our particular language, every day. It’s hard to get away from the commonplace, when you use the common language, and scribblers as a group generally feel envious of those whose language is music.